Moser’s Circle Problem - and why we still need GPs

December 20, 2023

Recently I was thinking about why GP training needs to take so long. Why can't we just replace GPs with reasonably smart people and computers?

It's a tricky question, but I stumbled across something from the world of maths which might be relevant.

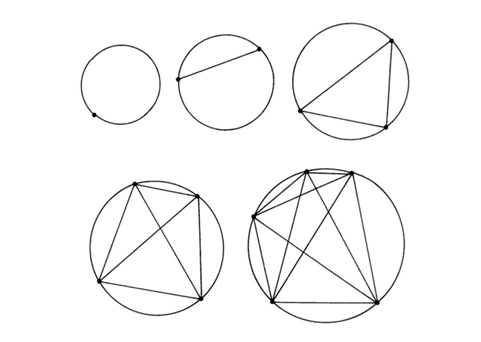

In the picture below are 5 circles. Each circle has a different number of dots on its edge. When you join all those dots with straight lines, you divide the circle into a number of areas.

How many areas are in each of these circles?

Well, if you count them, you will see that:

- The circle with one dot has just one area.

- The circle with two dots has two areas.

- The circle with three dots has four areas...

The relationship between dots and areas is like this:

| Dots | Areas |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 4 |

| 4 | 8 |

| 5 | 16 |

So let me ask you a question.

Q. How many areas will there be if there are 6 dots on the circle?

Hold that thought for a moment, and let me tell you about a few patients I made up.

An elderly lady, who has pain from a cracked rib. She felt it go when she leaned over a sofa arm six weeks back. It is painful to sneeze, and the pain is bothering her at night.

A fit man whose young kids always bring home a string of colds, but his cough seemed to have lingered far longer than anyone else’s and "gone to his chest" – he is keeping the whole house up with his coughing.

And a middle-aged farmer who has a flu like illness with dry cough, headache and aching limbs. It's been going on for a week already. Initially she took herself off to bed and it seemed to be getting better. But now things seem to be getting worse again.

These are all bread and butter primary care presentations, right?

The patient with rib pain will get better with ibuprofen and tincture of time. The man's chest infection will improve, but he may need a course of antibiotics. The patient with flu just needs to rest up and take paracetamol while she recovers.

But actually, no. That's not always what happens.

What if the bony pain is in fact due to multiple myeloma, a rare form of bone cancer? It needs chemotherapy, not ibuprofen.

What if the persistent cough is a sign of sarcoidosis, a rare condition where clusters of inflammatory cells called granulomas form in the lungs. It probably needs steroids, not antibiotics.

And what if the patient with flu-like symptoms has contracted Weils disease, leptospirosis, while working on the farm's water supply? What if it is entering the second, immune phase, which is a very bad thing, and her kidneys and liver are failing as millions of tiny clots form in her bloodstream? You can fix leptospirosis, but it is best recognised while the patient still has working kidneys.

I'm not trying to give anyone nightmares here. Those conditions are pretty rare. And happily, we have a pretty good healthcare system, through which even rare conditions like these tend to be diagnosed and treated in a timely fashion.

But have you paused to consider how this happens?

Clearly, things like bruised ribs and coughs and flu are common. They are like horses in a field.

On the other hand, things like myeloma, sarcoidoisis and leptospirosis are not very common. They may graze in the same field as the horses, but they are in fact zebras.

Zebras can be easy to recognise in broad daylight. The stripes are a dead giveaway, or "a strong visual cue" as some might say in medical education circles.

But broad daylight is not guaranteed in healthcare. Phone consultations for example, by stripping all visual cues, can sometimes make it feel more like night than day. And it's easy to miss a zebra in a field at night.

Even still, there may be something about the murky silhouette that doesn't sit well.

If the patient with painful ribs is also losing weight, why might that be? If this is the first time the young guy with the cough had troubled his doctor in fifteen years, what's that about? If the farmer with "flu" also had very dark urine- is that normal in flu?

These subtle discords, these incongruencies, these anomalies- they somehow resonate. A faint but discernible bell rings deep in the subconscious. The experienced doctor intuitively knows to pursue a particular line of enquiry or attention. To shine an inquisitive torch into the field, to make the zebra's form clearer. Which leads to accurate diagnosis, and to proper treatment.

Let's go back to the circle question. Can you guess where this is going?

Remember, the relationship between dots and areas goes like this:

| Dots | Areas |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 4 |

| 4 | 8 |

| 5 | 16 |

And The question is:

Q. How many areas will there be if there are 6 dots on the circle?

We all did a bit of maths at school, right?

It might be tempting to look at the pattern: 1, 2, 4, 8, 16; see the numbers doubling with each step, and conclude that the relationship between dots and areas is:

| 2^(n-1) |

|---|

In which case, the 6-dot circle should have 32 regions.

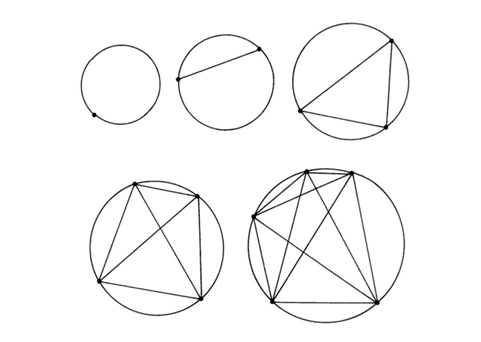

But actually no, that's not what happens.

The sixth circle only has 31 areas.

You can count them here:

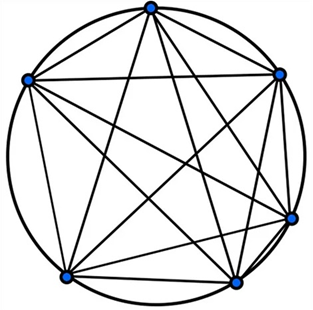

This is Moser's circle problem. It's a classic demonstration of the danger of "false induction": projecting something from a small sample, or limited knowledge.

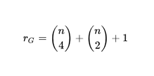

For those who are interested, the relationship is actually given as:

|

|---|

And the sequence continues like this:

| Dots | Areas |

|---|---|

| 6 | 31 |

| 7 | 57 |

| 8 | 99 |

| 9... | 163... |

How might a mathematician correctly "diagnose" the 6th circle as having 31 areas, not 32?

I suggest there are two main ways.

One way is by working from first principles. What causes a new area to be formed in Moser's circles? It can only be the division of an existing area by a line, by joining 2 dots; or the division of an existing line by another line, which requires the joining of 4 dots. And so it is possible to calculate the number of areas by considering out all possible lines and intersections (and take my word for it, the inductive proof is pretty hideous).

Another way is by experience. Having seen Moser's circle problem, if we encounter a rare 6-dot-circle in the wild, we will be probably simply remember that it contains 31 areas, not 32.

And maybe it’s like that when GPs encounter illness. Most of the time we deal with horses (to extend the metaphor; we are not vets).

But if we see enough undifferentiated equine presentations in primary care, sooner or later we'll see a zebra.

It takes a broad training to spot species we have not previously encountered, to question zebrahood when some aspect does not quite fit the horseshoe. To go back to the basics of physiology and pathology & run the various dots, lines and areas through our own complex mental models.

And even then, zebras can be really difficult to spot in a field of horses, at night.

This is one of the reasons why training a GP from medical school currently takes a minimum of 10 years. There are many animals in the zoo- please let me know if I’m working this metaphor too hard- and learning about them all takes a long time.

We draw on this hard-earned knowledge for illumination, in the same way that a mathematician might draw on their accumulated knowledge of geometry, algebra and combinatorics to solve Moser's circle problem. Or to shine light on some other problem in their field. At night.

It's not just about new presentations either. It's about recognising and dealing with normal and abnormal illness progression, treatment failures, unexpected outcomes, marginal cases, diverse and ever-expanding management options, calibrating risk, weighing and judging when to sit back, and when to act. The list goes on.

And crucially, a GP's decisions can be informed by a knowledge of the human in front of them, built up over time. Their background, their fears, their behaviour in the past. Subtle cues from their demeanour, voice, and body language.

This is why GPs represent the gold standard when dealing with undifferentiated medical presentations in the community.

New technologies will change the way we work, undoubtedly. And we should celebrate and embrace them. Every week wonderful new tools are emerging to help us recognise patterns, avoid pitfalls, and draw information together for the benefit of our patients.

They are getting better and better all the time, and they will allow us to be better and better too.

But will GPs eventually be replaced by reasonably smart people with computers?

It seems we are not there yet.

Leave a comment